Urhobo Historical Society

Quo Vadis (Oil) Resource Control in the Niger Delta?

By Emmanuel Ojameruaye, Ph.D.

Introduction

As

we approach the October 4, 2009 deadline for all militants in the Niger

Delta

to surrender to the Federal Government (FG), the question facing the

apostles

of (oil) resource control by oil producing states and communities is: quo

vadis?, i.e. "Where do you go from here ?" or simply

"What next?". Will the October 4, 2009 mark the end of the resource

control struggle or will it mark a pause? If it is the latter, when

will it

resurrect again and in what form?

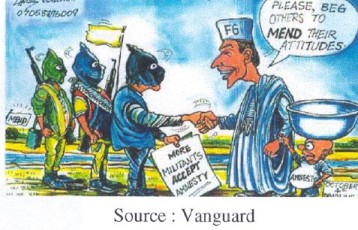

The Amnesty Deal

It is now an open secret that the Federal Government believes that

October 4,

2009 will mark the end of at least the military wing of the struggle.

In fact, the

Federal Government is already sounding triumphant and waving the

�Mission

Accomplished� banner. On September 29, 2009, the presidential review

meeting on

the implementation of the Amnesty program concluded that the October 4

deadline

for all repentant militants to surrender their arms remains unchanged.

The

meeting chaired by President Yar�Adua was attended by the

Vice-President, Chief

of Defense Staff, Inspector-General of Police, Governors of Cross

Rivers, Akwa

Ibom, and Bayelsa States, the Deputy Governors of Rivers and Delta

States,

Ministers of the Niger Delta Ministry and the Presidential Honorary

Adviser on

Niger Delta Matters.

The meeting completely ignored

the

conditions given by two leaders of the Movement for the Emancipation of

the

Niger Delta (MEND), Government Ekpemukpolo, aka Tompolo, and Ateke Tom

for

accepting the amnesty program. Tompolo had asked for an extension of

the

deadline by three months while Ateke had called for the withdrawal of

the Joint

Task Force (JTF) from the region. In fact, after the meeting the

Federal

Government categorically stated that it does not recognize MEND.

Briefing

State House Correspondents on the outcome of the meeting, the Defense

Minister

and Chairman of the Presidential Amnesty Committee, Major-General

Godwin Abbey

(rtd), warned MEND that it could not threaten the very existence of the

Federal

Republic of Nigeria. He noted that the government is prepared to defend

the

sovereignty of the country in all its ramifications. He said: �After

the 4th

of October the amnesty terminates, there will be no extension.

Government is

firm, is resolute and government will continue with subsequent aspect

of the

rehabilitation and reintegration of all those who have embraced

amnesty�MEND is

not recognized by the Federal Government as the spokesperson for the

militants

that is if they exist at all physically�MEND cannot choose for the

Nigeria

nation, if MEND decides to test the will of government and choose to

threaten

the very existence of the Federal Republic of Nigeria, government is

prepared

to defend the sovereignty of Nigeria in all its ramifications.�

On the next step by the Federal

Government (FG) after the deadline

of the amnesty offer, the minister said: �Government is going to

pay

attention to all the militants who have embraced amnesty; they are

going to be

put together in various camps that have been designated and in this

camps they

will be categorized and personal contacts will be established with each

of them

after thorough documentation and their choice of training and

settlement will

also be identified�.Government is willing to train them and to join

them in any

rehabilitation effort that will bring about their going into life as

normal

citizens without resorting to militancy.�

The meeting did not address the

issue of resource control which

has long been recognized as the root cause of the militancy. In fact,

despite

calls on the FG to address the resource control issue as part of a

holistic and

sustainable approach to addressing the Niger Delta crisis, it has

remained

silent on the issue before and since the declaration of the Amnesty

program. In

fact, a day before the above-mentioned meeting, MEND announced that

Nobel

laureate, Prof. Wole Soyinka, and Vice Admiral Mike Akhigbe (rtd) had

agreed to

join its four-man �Aaron team� of mediators with the FG. MEND

stated that

�Some eminent Nigerians have graciously accepted to dialogue on

behalf of

the Movement for the Emancipation of the Niger Delta, MEND, with the

Federal

Government of Nigeria whenever the government realizes the need to

adopt

serious, meaningful dialogue as a means to halting the violent

agitation in the

Niger Delta�. MEND further stated that the mediators �have

our

mandate to oversee a transparent and proper MEND disarmament process

that

conforms with international standards as the current disarmament

process is

flawed and lacks integrity�The MEND disarmament process will only come

after

the root causes of militancy and agitation in the Niger Delta have been

addressed by the Nigerian government�. MEND went further to accuse

the FG

of not showing �willingness to dialogue, preferring instead to make

wild

unrealistic threats, purchase more useless military hardware, and dole

out

bribes to traitors to our noble cause."1

Obviously, from

the statement

of Gen. Abbe after the presidential meeting, it is clear that the FG is

not

interested in negotiating with the MEND�s team. The FG appears

confident that

the Amnesty program has crippled MEND. The FG is also appears set for a

major

offensive against those militants who refuse to surrender by the

October 4

deadline. It has been reported that as soon as the FG announced the

Amnesty

program it began preparation for a new offensive in the creeks.

According

to the reports, Israeli and Russian instructors have been "providing

specialized training to Nigerian Navy and Air Force sailors and pilots

on how

to operate the ships and helicopters over the past few months, and some

of

these instructors may help operate them during the offensive."

It

is instructive to note that ever since the Amnesty debate started, the

FG has

not clearly stated how it plans to address the �root causes�of the

violence in

the region other than repeating the usual refrain : �we

will develop the region.� It appears that the FG and MEND have

different views on the �root causes� of the crisis. To the FG, it

appears that

once the �repentant� militants can be settled by cash payments,

training and

rehabilitation all will be well. To MEND, the root cause is the refusal

of the

FG to acquiesce to the demand for resource control. However, MEND

leaders have

not been using the term �resource control� lately and it is becoming

doubtful

if most of the militants and some of their leaders know what resource

control

is all about or have a coherent goal for their struggle. Now that the

militancy

now appears to be in its �last throes�, at least for some time, what

will

happen to �resource control� struggle?

Let

me observe that the term �resource control� seems to have fallen into

disuse in

recent times. The FG as well as political leaders from the Niger Delta

region

and even the militants hardly use the expression these days. To the FG,

it has

almost become an anathema because it is synonymous with rebellion. Many

political leaders from the Niger Delta seem to have also decided to

keep away

from the expression after claims by some governors from the region that

their

�travails� (and �punishment�) under President Obasanjo was due to their

leadership of the resource control struggle. Since most

politicians are

more interested in �personal preservation and interest� they seem to

have

decided to stay away from being associated the struggle.

Evolution

of the Resource Control Struggle

To

predict the future of the resource control struggle, it is important to

first

define the concept and do some �backcasting�. Although the struggle for

resource control in the Niger Delta can be traced to colonial times,

the term

was not used then. In fact, the term was first used by the

�South-South�

governors in 2002 during �offshore/onshore dichotomy� case between the

FG and the

littoral states at the Supreme Court. It was during the heat of

the

offshore/onshore court case, that the SS governors met in Benin City

and

defined their struggle as ultimately one of �resource control� which,

they

defined as:

"The practice of true

federalism

and natural law in which the federating units express their rights

to

primarily control the natural resources within their borders and

make

agreed contribution towards maintenance of common services of sovereign

nation

state to which they belong. In the case of Nigeria, the federating

units are

the 36 states and the Sovereign nation is the Federal Republic of

Nigeria�.

The Governors were simply

recanting statements contained in

previous Bills of Right, Declarations and Charters of Demand by some

ethnic

nationalities in the region such as the Ogoni Bill of Rights, The

Kaiama

Declaration, etc. For instance,

the

�Ogoni Bill of Rights� presented to the federal military government and

peoples

of Nigeria in November 1990 included the following: �i)

That oil was struck and produced in

commercial quantities on our land in 1958 at K. Dere (Bomu oilfield);

ii)

That in over 30 years of oil mining, the Ogoni nationality have

provided the

Nigerian nation with a total revenue estimated at over 40 billion Naira

(N40

billion) or 30 billion dollars; iii) That in return for the above

contribution, the Ogoni people have received NOTHING; iv) That the

Ogoni people

wish to manage their own affairs; v) That the Ogoni people be granted�The

right to the control and use of a fair proportion of OGONI economic

resources

for Ogoni development; �The right to protect the OGONI environment

and

ecology from further degradation.

The

Ogoni Bill of Rights brought some of Ogoni leaders into direct

confrontation

with the federal military government which led to a �military

occupation� of

Ogoni territory. Following internal feud within the ranks of Ogoni

leadership

which lead to the brutal murder of some Ogoni leaders, nine activists

of the

Movement for the Survival of Ogoni People (MOSOP) including its leader,

Mr. Ken

Saro-Wiwa, were hanged by the Abacha military regime on November 10,

1995

despite pleas for clemency by several world leaders and oil company

executives.

On

the other hand, the 1998 "Kaiama Declaration" by the Ijaw Youth

Council (IYC) states inter alia that: �all land and natural

resources

within the Ijaw territory as belonging to the Ijaw communities� because

they

are the basis of our survival� peoples and communities right to

ownership

and control of our lives and resources".

In

essence, resource control, natural resource control within the Nigerian

context

is the desire of a state government and/or local government and/or

local

community to control any natural resource found within its defined

boundaries.

The degree of �control� is negotiable with the federal government.

Resource

control is different from derivation which is simply �a form of

compensation

and/or reparation for an expropriated interest�.a recognition of

a prior

beneficial right that was subsequently expropriated� (Akpo

Mudiaga-Odge).

In other words, under derivation, the federal government retains

control of

natural resources but compensates the state and local governments where

such

resources are exploited in accordance with an agreed formula. On the

other

hand, under resource control, the state and local governments are not

recompensed for anything; they collect the revenues (in terms of rents,

royalties, taxes and other payments) and pay agreed taxes (or

contributions) to

the central or federal government for its common protection and

administration

of the federation. The Nigerian constitution from colonial times to

date

provided for the principle of derivation and not resource control.

However, some

form of resource control has been in practice in mining of marble in

Igbeti

Community in the old Western Region (now Oyo State)2

Given the political economy of Nigeria and the practical difficulties

of

implementing resource control of natural resources by regional or state

governments, the country had settled for the principle of derivation

since

colonial times. This does not mean that it is the ideal system for a

true

federation and that other options cannot be adopted with the passage of

time.

For instance, it is possible to adopt �joint ownership� or control of

natural

resources by both the federal government and the mineral producing

state and

local governments and communities through the allocation of shares or

equity

holding in mineral producing ventures to the latter group similar to

the Igbeti

Marble Formula. This way, state and local government as well

communities can

participate in the management, control and �dividends� of the mineral

activities

within their territories.

To

be sure, the issue of revenue sharing or allocation (and hence degree

of cross-subsidization)

has been a thorny one since the foundation of Nigeria. According to the

2006 UNDP

Human Development Report for the Niger Delta, �At the root of the

amalgamation of the Southern and Northern Protectorates by Lord Luggard

in 1914

was the issue of cross-subsidization � the richer South would subsidize

development endeavors in the poorer North. The level of

cross-subsidization was

not specified�in 1946�the Phillipson Fiscal Commission �proposed the

derivation

principle as a basis for fiscal federalism. The idea was that revenue

should be

shared, among other things, in proportion to the contribution each

region made

to the common purse or central government. Derivation became the only

criterion

used to allocate revenues among the regions in the 1948-1949 and

1951-1952

fiscal years. In the period shortly after independence in 1960, the

disparity

in allocation largely reflected the degrees of enterprise and levels of

production in the regions. This means that, by merely looking at the

levels of

allocations, one could easily discern the regions with high levels of

economic

activities in areas such as cash crop production�earnings from exports

and

excise duties, etc. The incentives embedded in the revenue allocation

inevitably encouraged competition among the regions, with each striving

to

contribute more in order to get more from the centrally allocated

revenues.

Between 1946 and 1960, the derivation principle was maintained at 50%.

After

independence, it continued at the same level until 1967, when the

Nigerian

civil war started�After the civil war led to the political and fiscal

centralization of the federal system, the military administration of

General

Gowon promulgated the Petroleum Decree No. 51 in 1969. This put the

ownership

and control of all petroleum resources in, under or upon any land in

Nigeria

under the control of the Federal Government. It means that individuals,

communities, local governments and even states with land containing

minerals

were denied their rights to the minerals�. Consequently, derivation

plummeted progressively from 50% in 1967 to 20% (minus offshore

proceeds) in 1975-79,

then to 0% in 1979 -1981, 1.5% in 1982-1992, 3% in 1992-1999 and the

13%

(minimum) under the 1999 Constitution that the military regime handed

over to

the new civilian administration of President Obasanjo. However,

President

Obasanjo initially refused to apply the 13% derivation he inherited to

offshore

proceeds thereby effectively reducing it to less than 8%. Do we

need to

look any further for the underlying cause of the twelve-day (Niger

Delta

Republic) revolt led by Major Isaac Adaka Boro in 1966 and the clamor

for

increased derivation since the early 1980s which has boiled over into

clamor

for resource control and unrest in the Niger Delta region?

As

a result of the struggle for resource control by the governors and

political

leaders of the Niger Delta, the FG under President Obasanjo decided to

abolish

the offshore/onshore oil dichotomy in 2004 thus paving the way for the

allocation of the 13% of oil revenue to the oil-producing states in

accordance

with the 1999 constitution. Not satisfied, the leaders carried the

struggle to

National Political Reform Conference (NPRC) convened by President

Obasanjo in

early 2005. However, because of the limited mandate of the NPRC, the

Niger

Delta delegates apparently decided to focus on increasing the

percentage

derivation instead of pressing for resource control. As a starting

point, the

Niger Delta delegates to the NPRC demanded for 60% derivation but they

eventually

settled for �25% now and 50% within 5

years�, i.e. a return to the 1963 position within five years.

However, the

majority delegates from other part of the country, particularly from

the North,

insisted on 17% derivation which was eventually adopted by the NPRC. At

the end

of its deliberations in July 2005, the NPRC made the following

recommendations

amongst others:

i) "an expert

commission should be appointed by the Federal Government to study all

the

ramifications of the industry including revenue allocation with a view

to

reporting within a period of not more than six months, how the

mineral

resources concerned can best be controlled and managed to the benefit

of the

people of both the states where the resources are located and of

the

country as a whole�.

ii) "A clear

affirmation of the inherent right of the people of the oil

producing areas

of the country not to remain mere spectators but to be actively

involved in the

management and control of the resources in their place by having

assured

places in the Federal Government mechanisms for the management of the

oil and

gas exploration and marketing.

iii) increase in the

level of derivation from the present 13% to 17%, in the interim pending

the

report of the expert commission. Delegates from the South-South and

other

oil producing states insisted on 50% as the irreducible minimum.

Having

regard to national unity, peace and stability, they agreed to

accept, in the

interim, 25% derivation with a gradual increase to attain the 50% over

a period

of five years.

Following

the NPRC, there was a lull in restiveness the region as the militants

and

proponents of resource control waited for President Obasanjo to

implement the

above recommendations. However, when it became clear that the President

was not

in a hurry to implement the recommendations, the militants resumed the

struggle. This time around the �struggle� became more violent because

of: (a)

the arrest and detention of Alhaji Mujahid Dokubo-Asari, the �Supreme

Leader�

of the NDPVF and Chairman of the Niger Delta People�s Salvation Front

(NDPSF)

in October 2005 on charges of treason; and (b) the impeachment of the

Governor

of Bayelsa State, Chief D. S. P Alamieyeseigha, in early December 2005.

He was

detained in London in November on charges of money laundering but he

jumped

bail and escaped to Nigeria and was subsequently expelled from the PDP

and

impeached by the State Assembly, an action that was believed to have

been

orchestrated by President Obasanjo, as payback for championing

�resource

control� and supporting the militants.

The

rank and profile of the militants increased significantly as a result

of the

two factors mentioned above. They demanded for the release of both

Alhaji

Dokubo-Asari and Chief Alamieyeseigha but President Obasanjo refused to

yield

to their demands. In addition, he also refused to implement the

recommendations

of NPRC on the Niger Delta. Thus, the oil-producing areas continued to

receive

13% of oil revenue as against the 17% recommended by the NPRC till he

left

office in May 2007 and up till today.

In

an attempt to reduce tension in the region, President Obasanjo

inaugurated the

Council on the Socioeconomic Development of Coastal States of the Niger

Delta

on April 18, 2006 with himself as the Chairman. In his address to the

Council,

he outlined a 9-point agenda for the region, including the creation

20,000 new

jobs in the Armed Forces, Police, NNPC and Teaching for indigenes of

the region

within three months, commitment of N230 billion for the construction of

the

long-abandoned East�West (Warri-Mbiama- Port Harcourt-Eket-Oron) road,

commencement of the dredging of the river Niger, upgrading of the

Petroleum

Training Institute (PTI), Effurun in Delta State to a degree-awarding

institution, establishment a federal polytechnic in Bayelsa State by

September,

rural electrification for 396 communities, water supply for over 600

communities, and the appointment of an officer in the office of the

Secretary

to the Government of the Federation to coordinate the various

intervention

programs by all the tiers government as well as those of oil companies

and

development partners. The Council turned out to be another ruse as most

of the

promises were not delivered before he left office. However, he

established a

new Federal University of Petroleum Resources in Effurun on the eve of

his

departure from office and appointed Prof. Alabi from his home state

(Ogun) as

Vice Chancellor, Mrs. Onwuka from the South East as the Registrar, and

the Emir

of Gwandu from the North as the Chancellor, and Engr. Makoju, also from

the

South West, to head the Governing Council. The President did not deem

it fit to

appoint a Niger Deltan as one of the principal officers of the new

university

located in Delta state.

The

Faltering of the Resource Control Struggle

By

the time President Obasanjo left office in amy 2007 he had almost

neutralized

the �political wing� of the resource control struggle through

intimidation of

the governors, legislators and other politicians aspiring to �elective�

and

appointed political offices, especially under the ruling PDP party.

After the

travails of some governors, many politicians from the area decided to

either

avoid using the term �resource control� or soft-pedal on the issue of

resource

control for fear of being �EFCC�ed�. Ironically, as the political

leaders made

a tactical withdrawal from the struggle, the �military wing� grew

stronger and

attracted a larger number of unemployed youths, some of whom were used

to rig

the 2007 elections by the politicians. At the same time, the militants

started

making money through illegal oil bunkering (stealing of crude oil),

hostage taking,

harassment of oil companies and forced protection payments from oil

companies.

With the money coming in from these sources, the leaders of the

militants were

able to procure more arms and recruit more

militants.

As soon

as

President Yar�Adua was sworn into office in May 2009 he correctly

identified

the resolution of Niger Delta crisis as one of his cardinal objectives.

However, rather than move quickly to implement the recommendations of

previous

commissions on the Niger Delta, he opted to hold his own form of Niger

Delta

Summit under the leadership of Prof. Ibrahim Gambari. The people of the

Niger

Delta saw the move as a deceptive tactic to resolving the resource

control

issue, and unanimously rejected the idea of the Summit under the

chairmanship

of a Northerner. President Yar�Adua thus retreated and after some

prevarications established the 44-member Niger Delta Technical

Committee (NDTC)

in September 2008 under the chairmanship of Dr. Ledum Mittee, the

leader of

MOSOP, with members drawn from all the Niger Delta states. The

Committee was

charged to: a) collate, review and distill the various reports,

suggestions

and recommendations on the Niger Delta from the Willinks Commission

Report

(1958) to the present and give a summary of recommendations necessary

for

government action; b) appraise the summary recommendations and present

a

detailed short, medium and long term suggestions to the challenges in

the Niger

Delta; and c) make and present to government any other recommendations

that

will help the Federal Government achieve sustainable development,

peace, human

development and environmental security in the Niger Delta region�.

The NDTC

completed

its assignment in November 2008 and submitted its report to the Federal

Government in December 2008. The report contained far-reaching

recommendations aimed

at the �sustainable development, peace,

human development and environmental security� if they are all

implemented

as a �package�, i.e. holistically. The Committee noted that �the

very

first action by the government towards implementing these

recommendations is

even more important than any other subsequent

intervention�Consequently, the

recommendations are set out as two inter-related parts; the first part

being

those actions that set the right tone for the implementation of all

subsisting

and further actions. The tone-setting agenda appears �in the form of a

Compact

with the Niger Delta� The short-term Compact will deliver on a visible,

measurable outputs which produce material gains within an 18 months

period�guided by a principle in which the Federal Government�.report

publicly

on progress in implementation every three months�. Among

other things

the Compact aims to deliver the following within an 18 month period: a)

Immediately

increase allocation accruing from oil and gas revenues to the Niger

Delta to

25% (i.e. additional 12%)�b)Within 6 months, complete initial steps

that will

support a disarming process for youth involved in militancy. This

process would

have to begin with some confidence building measures on all sides.

These

measures include cease fire on both sides, pull back of forces, open

trail of

Henry Okah. Also credible conditions for amnesty, setting up a

Decommissioning,

Disarmament and Rehabilitation (DDR) Commission and a negotiated

undertaking by

militant groups to stop all kidnappings, hostage taking and attacks on

oil

installations; c) Establish by the middle of 2009, a direct Youth

Employment

Scheme (YES) in conjunction with states and local governments

that will

employ at least 2,000 youths in community works in each local

government of the

9 states of the Niger Delta; and d) Complete the East-West road

dualization

from Calabar to Lagos by June 2010�

Even

before the

NDTC completed its work, the Federal Government went ahead to announce

the

establishment of the Ministry of the Niger Delta which was not part of

the

Compact. Critics regarded the establishment of the Ministry as a

cosmetic and

sinister move because that was not the issue at stake. It was argued

that the

creation of the Ministry would increase the bureaucratic red tape in

resolving

the Niger Delta crisis, weaken (and crowd out) the NDDC and the

authority of

the state governments. In view of the short deadline given to the NDTC

to

complete its work and the sense of urgency in resolving the Niger Delta

crisis,

it was expected the Federal Government would present the NDTC report to

the

National Assembly and then issue a White Paper on it and commence the

implementation

of the recommendations immediately. In fact, it appeared that after the

establishment of the Ministry of the Niger Delta, President Yar�Adua

went to

sleep and kept the NDTC report on his shelf to gather dust. By April,

2009 it

had become clear that the Federal Government was not interested in

implementing

the recommendations of the NDTC. Meanwhile, the agitation in the Niger

Delta

continued unabated as the FG used its Joint Military Task Force (JTF)

to

intensify its fight against the militants. At the same time, there was

growing

comingling of militancy with criminality as some militants intensified

kidnappings, hostage taking, attack on oil installations, etc. Even

many Niger

Deltans became worried by the growing insecurity in the region caused

by the

activities in the militants. There were growing signals that the FG was

leaning

more towards a �military solution� to the crisis. All that the

government

needed was a �trigger�. Whilst waiting for the trigger, the FG

decided to

set up an 18-member Presidential Panel on Amnesty and Disarmament of

Militants

in the Niger Delta (PPADM) on May 5, 2009 under the chairmanship of the

Minister of Interior, Major-General Godwin O. Abbe (rtd), with the

following

terms of reference: a) To prepare a step-by-step framework for

amnesty and

complete Disarmament, Demobilization and Re-integration (DDR) in Niger

Delta

with appropriate time-lines; b) To ensure that those with criminal

records do

not take advantage of the amnesty; and c) To work out the cost to

Government of

disarmament, demobilization and re-integration of the militants.

It

should be noted that the NDTC called for the establishment of a DDR

Commission

within 6 months, but the FG decided to set a �Panel� on �Amnesty and

Disarmament� about six months after it received the NDTC

report.

Even at that, the Panel did not start work until after the �trigger�

came on

May 13, 2009 when the JTF launched a full-scale invasion on the Ijaw

Gbaramatu

Kingdom in Delta State to dislodge �Tompolo�and his fellow MEND

militants who

had allegedly killed some members of the JTF. As the JTF continued its

offensive against the militants, the FG began working on the terms of

�amnesty�

for the militants under a sense of �mission accomplished�. The

Presidential

Panel completed its work at about the third week of June and submitted

its

63-page report to the FG recommending a N50billion amnesty package for

�repentant militants�. President Yar�Adua made the Amnesty Proclamation

on June

25, 2009. However, two days before the proclamation, security agents

arrested

the leader of the Niger Delta Volunteer

Force, Asari

Dokubo on his return from a medical trip to Germany but he was

quickly

released on orders of the President to demonstrate his

�magnanimity�. A day before the

proclamation of the Amnesty,

MEND accused the Head of the Presidential Panel on Amnesty for

Militants

in the Niger Delta, General Godwin Abbe (rtd), of trying to bribe them

in order

to get their cooperation in sharing the N50 billion budgeted for the

amnesty

exercise. MEND spokesman, Jomo Gbomo, was quoted as saying �It

is a

shame that the interior minister and his cohorts are offering bribes

and

incentives to militants in a desperate attempt to get our cooperation

in

sharing the N50 billion budgeted for the amnesty exercise�.While it is

true

that some of us will succumb to the temptation of money as Judas did,

there are

a majority that will remain steadfast in integrity, honor and a

commitment to

the people who cannot fight for their rights.�

Later,

the FG

released Henry Okah, one of the militant leaders who had been in

federal custody

for over a year, to travel abroad for medical attention. At the same

time, the

FG announced that each militant who came forward to surrender at the

will be

aid N20,000 monthly plus N1,500 daily for meal, making a total of

N65,000

monthly. The �monetary bait� was aimed at incentivizing the militants

to give

up their arms and surrender to the JTF. To further shore up

confidence

for the amnesty plan, President Yar�Adua made a one-day visit to

Yenegoa, the

capital of Bayesla state. Amidst apprehension and counter-accusations,

the

amnesty came into effect on August 6 and militants were given 60-days

up till

October 4, 2009 within which to surrender their arms to the FG and be

registered for post-amnesty rehabilitation. After initial hesitation,

many of

leaders of the militants, starting with �General� Boyloaf�, began

accepting the

amnesty due mainly to monetary incentives and pressure from some

political

leaders from the region. The leaders of the militants encouraged and

their

�boys� to come forward to submit their arms and ammunitions. Despite

several

hiccups, over 6,000 out of the expected 10,000 militants have

surrendered to

the FG as of September 29. However some MEND leaders such as Dokubo

Asari and Jomo

Gbomo are yet to fully embrace the amnesty. It is doubtful if the MEND

leaders

who have not fully embraced the Amnesty can be as effective after

October 4 as

they were before the Amnesty. For one thing, the Amnesty seems to have

torn the

militancy asunder by putting a knife in the fragile bond that held the

militants together. In fact, it appears that for the militants �things

have

fallen apart and the center can no longer hold�.

From all

indications, it will be difficult for militants to regroup and

constitute a

threat to the FG in the immediate future. Since the FG did not make a

commitment to resolving the resource control issue after the amnesty,

one can

safely say the �military wing� of the resource control struggle seems

to have

lost the battle, but perhaps not the war. The political wing lost the

battle

much earlier. Since the past two years, most political leaders hardly

use the

word �resource control�. At best, they talk of addressing the �root

causes� of

the crisis by calling on the FG to develop the region through

infrastructural

development and job creation. Neither President Yar�Adua nor the

Chairman of

the Amnesty Implementation nor the Niger Delta Ministry nor any of the

governors has mentioned resource control or the implementation of the

NDTC

report since the declaration of the Amnesty. Now that both the

political and

militant wings of the resource control struggle seem to have

back-pedalled on the resource control

issue, quo

vadis?

The

Future of

the Resource Control Struggle

It is

difficult to

predict the future course of the resource control struggle. There are

various

possibilities. The FG can put a permanent end to the struggle by taking

certain

actions far beyond the proposed post-amnesty rehabilitation of the

repentant

militants.

Firstly,

if the

Amnesty succeeds and a development-enabling environment is created in

the

region over the next six months, the FG may decide to implement all the

recommendations of the NDTC which will address a significant part of

the �root

causes� of the crisis, and the ultimate goal of the resource control

issue.

Will this happen?

Secondly,

the FG

may decide to implement some of the recommendations of the NDTC plus

other

recommendations that will fully address the resource control issue.

These

include: i) incrementally increasing derivation to 50%; or ii) adopting

an

incremental-differential derivation formula; or iii) adopting the

�Igbeti

marble formula� by allocating share (equities) in oil

companies/ventures to oil

producing states, local governments and communities; iv) combining

increased

derivation (to, say, 25%) with equity holding by oil producing

areas in

oil ventures (to, say 25%); and v) establishing a petroleum

heritage and

dividend fund for oil producing states, etc.3

On the

other hand,

the FG may assume that the resource control struggle is dead and then

decide to

ignore the NDTC recommendations, implement the Amnesty program for some

time

(i.e. resettle the repentant militants) and continue business as usual,

i.e.

retain the 13% derivation, and withdraw the JTF after sometime. It is

unlikely

if this scenario will result in sustainable peace and development in

the

region. For one thing, the projected 10,000 �repentant militants�

constitute

only about 0.2% of the youths in the region and less than 1% of the

number of

unemployed youths in the region who constitute ready recruits for a

future

�military wing� of the resource struggle.

Alternatively,

the

FG may decide to ignore the NDTC recommendations, implement the Amnesty

program

for some time, continue business as usual and treat the region as a

conquered

territory, i.e. expand and retain the JTF sine die. This course

of

action will not be sustainable under a democratic setting. Under this

scenario,

the �political wing� of the resource control struggle will wake up from

its

current slumber, liberate itself from the ruling PDP and align with

other

parties in the country that are willing to address the resource control

issue.

If they fail to find allies, they may take the gauntlet and align with

a new

group of more disciplined militants. The outcome of this can be

anybody�s

guess.

Lessons

and Recommendations

What

then are some of the lessons of the resource control struggle to date?

Firstly,

a situation where the exploitation of a natural resource (hydrocarbon)

with

significant negative externalities (such as pollution, environmental

degradation and loss of farmlands) takes place in a certain region of

the

country and the federal government appropriates over 85% of the revenue

coming

from that resource is a recipe for instability and insecurity, and a

time-bomb

at worst.

Secondly,

natural justice and common sense dictate that at least 50% (but

preferably

100%) of rents and royalties paid by ventures that exploit a natural

resources

should be made to the people (state, local government, community and

individuals) from where the natural resource is exploited. The FG could

have a

share but not necessarily the loin share.

Thirdly,

the people on whose land a natural resource is exploited should not be

expected

to be mere spectators in the business. They have an inalienable right

to

participate in the management, ownership, control and dividends of the

ventures

that exploit the natural resource.

Fourthly,

the resource control struggle can be suppressed for some time, but not

all of

the time. So long as the natural resources of the federation are

distributed unevenly

and the benefits of the natural resource are not distributed to reflect

their

geographical locations the ghost of resource control will continue to

haunt the

federation. A high degree of cross-subsidization of one section of the

federation by another section is unsustainable in a federation. The FG

should

as a minimum return progressively to the pre-1967 revenue allocation

system.

Alternatively, as a minimum, it should adopt a system that ensures a

sense of

partial ownership and control of the exploitation of the natural

resource by

the state and local government areas where such a resource is found.

Fifthly,

the political leaders of the region where a natural resource is

exploited

should not be na�ve to think that a leader from the rest of the country

will be

so altruistic to grant resource control without a persistent struggle.

The

struggle must however be peaceful and unrelenting. If the political

leaders

abandon a peaceful struggle they create room for militants to take over

the

struggle. The �militant wing� is however susceptible to infiltration by

criminal elements and opportunists whose activities could lead to

alienation

and support of some of the very people they are purportedly fighting

for.

Thus, the militant wing must be disciplined and must be willing to work

cooperatively the political leaders of the region and the nation to

achieve the

goals of resource control.

Conclusion

In

conclusion, unless the �root causes� of the Niger Delta crisis are

addressed by

the FG, including the resource control issue, whatever peace the

ongoing

Amnesty program will bring may be ephemeral. As I concluded in

chapter 16

(The Long Road to Resource Control in the Niger Delta) of my book, The

Political economy of Oil and other Topical Issues in Nigeria,

�Following his

triumphant release in 1990 from more than a quarter-century of

imprisonment,

Mandela published his autobiography in 1994 which he aptly titled Long

Walk

to Freedom where he �tells the extraordinary story of his life -

an epic

of struggle, setback, renewed hope, and ultimate triumph�� Although

the

resource control struggle by the ethnic minorities in the Niger Delta

is

different (from Mandela�s struggle) in many respects, the few parallels

are

nonetheless poignant.

Emmanuel

Ojameruaye, PhD.

Phoenix, USA.

October

2, 2009

_________________

1 In a strange

twist, as I was about posting this article on the internet on October

2, the

Guardian of the same day reported that Tom Aleke was flown to Abuja the

previous day to meet with President Yar�Adua where he promised to

surrender.

2

The "Igbeti Marble formula" was first introduced in old Western

Region. It stipulated that "the proceeds of all resources in a

location should be shared to recognize the right of indigenous

communities, the

local, government, the operating firms, the state government and the

federal

government. This formula enables the local community to go into

partnership

with the technological firms producing wealth in the environment and by

participatory decision making in the process entails those concerned

share the

pride of progress together. The " Oyo State benefit plan" of 1990

also ensures that the people of the state derive maximum

benefit from

the exploitation of natural resource of the state by allocating of 10%

equity

participation to the state government."

(see A. A. Ikein, Socio-economic and environmental

challenges in

the Niger Delta.).

3 Details of these options for addressing the

resource control issue are contained in my submission to the NDTC in

September

2008 as well as in my presentation on �Preconditions for Sustainable

Peace and

Development in the Niger Delta region� at the Launching of the Niger

Delta

Congress in New York on July 12, 2009. Some details can also be found

in my

book, The Political Economy of Oil and other Topical Issues in Nigeria�

(Xlibris, 2006).